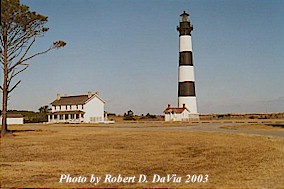

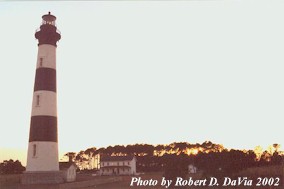

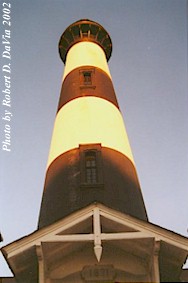

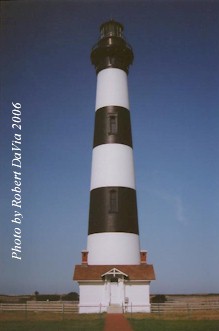

THE BODIE ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE

Click here for April 2006 Pictures

(The following is from a National Park Service handout, revised June, 2002)

BODIE ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE FACTS

HEIGHT: 156 Feet

HEIGHT OF STRIPES: 22 Feet

STAIRS: 214

LIGHT PATTERN: 2.5 seconds on,

2.5 off, 2.5 on, 22.5 off

BEAM RANGE: 19 Miles

OWNERSHIP: transferred from

US Coast Guard to the

National Park Service in 2000

Throughout history, the watery perils that exist off North Carolina's coast have endangered mariners. Hundreds of ships have fallen prey to these formidable currents, fierce storms, and shifting shoals...the infamous Graveyard of the Atlantic. The Outer Banks were an area crucial for the construction of lighthouses. Like so many other features here, the Bodie Island Lighthouse owes its very existence to these menacing waters.

In 1837, the federal government sent lieutenant Napoleon L. Coste of the revenue cutter Campbell to examine the coastline for potential lighthouse sites that would supplement the existing one at Cape Hatteras. Coste determined that south-bound ships were in great need of a beacon on or near Bodie Island, by which they could fix their position for navigating the dangerous Cape. He punctuated his recommendation with the statement that "more vessels are lost there than on any other part of our coast."

Congress responded with an appropriation for a lighthouse that same year, but complications over purchasing the necessary land delayed construction until 1847. This was but the first of many problems. Though the skillful Francis Gibbons was contracted as engineer, the project's overseer was a former Customs official named Thomas Blount, who unfortunately had no lighthouse experience at all. This proved disastrous when Blount ordered an unsupported brick foundation laid, despite Gibbons' recommendations to the contrary. As a result, the 54-foot tower began to lean within two years after completion. Numerous expensive repairs failed to rectify the problem, and the lighthouse had to be abandoned in 1859.

The second lighthouse fared little better than its wobbly predecessor. Though funded, contracted, and completed in prompt fashion at a nearby site it 1859, it soon succumbed to an unforeseen danger: the Civil War. Fearing that the 80-foot tower would be used by Union forces as an observation post, retreating Confederate troops blew it up in 1861.

After the war, the coast near Bodie Island remained dark for several years while a replacement tower was considered by the Lighthouse Board. Though the Board was disposed against the idea, numerous petitions came in from concerned ship captains, and finally it decided in favor of a third Bodie Island Lighthouse. Still, it was not until 1871 that construction began. The first two "Bodie Island" Lights had been located south of Oregon Inlet, actually on Pea Island. The new 15-acre site, purchased by the government for $15,000 from John Etheridge, was north of the inlet. Work crews, equipment, and materials from the recent lighthouse project at Cape Hatters were used to build necessary loading docks, dwellings, and facilities. Government contracts brought bricks and stone from Baltimore firms, and ironwork from a New York foundry. Construction of the tower proceeded smoothly, and it first exhibited its light, magnified by a powerful First Order Fresnel Lens, on October 1, 1872. The Keeper's Quarters duplex was completed soon thereafter.

Early problems with flocks of geese crashing into the lens and improper grounding for electrical storms were quickly rectified with screening for the lantern and a lightning rod for the tower. There have been few other difficulties with the lighthouse itself since its completion. From the keeper's perspective, however, there remained the problem of isolation. Bodie Island was completely undeveloped, and the closest school was in Manteo on neighboring Roanoke Island (accessible only by boat). This meant that the keeper's wife and children lived away from the lighthouse except during the summer months, making for a lonely and trying family life most of the year. Such situations, of course, were quite common in the Lighthouse Service. Eventually, progress enabled school buses to reach the island, and the families were able to live with the keepers.

The light was electrified in 1932, which finally ended the need for an on-site keeper. Finally, all of the light station's property except the tower itself were transferred to the National Park Service in 1953. The Keeper's duplex has since undergone two historic restorations, the last having been completed in May 1992. The building now serves as a ranger office and visitor center for Cape Hatters National Seashore. Still a functioning U.S. Coast Guard navigational aid, the tower remains closed to the public.

Tucked away between tall pine trees and freshwater marshland, the Bodie Island Light presents anything but a typical lighthouse setting. Though not as well-known as its neighbors, it remains an important part of local history, and a favorite spot for visitors. And still every evening, amidst the water towers and blinking radio antennae of modern development, its powerful beam sweeps out across the darkening waves, keeping silent watch over the treacherous waters know as the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

The following pictures were taken in April 2006

Return to the North Carolina State Page

Return to the: Alphabetical Listing or the Listing by States